He-Man’s Ripped Muscles Fueled My Eating Disorder and Body Dysmorphia

I was a college gym rat, hooked on binge eating, believing I needed to be muscular like my childhood hero, not suffering from stretch marks and stomachaches

It was starting. Lightning bolts streaked across the screen! A cartoon prince shouted and thrusted a glowing sword into the cracked sky! Yesssssss! My shuddering frail body pulsed with excitement. As a five-year-old boy in 1984, He-Man was my man. He promised transformation to a generation of young boys—from whiny privileged punks into proud humble warriors.

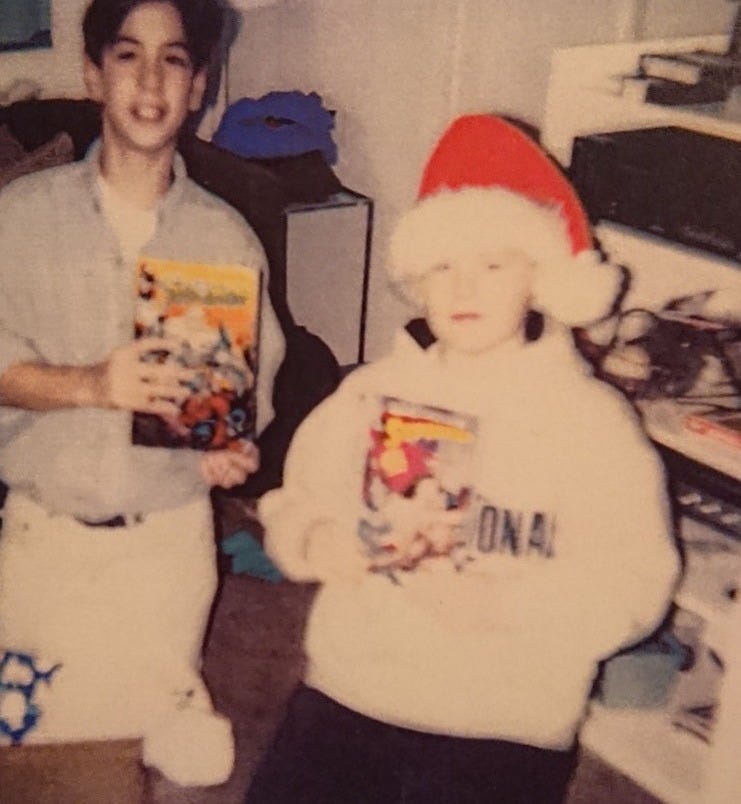

I reacted exactly how Mattel predicted. I gotta get a sword! So I headed over to James’s house. Born four months apart, James was my moody, freckle-faced stocky neighbor. We grew up pretending to be He-Man and Conan the Barbarian or taking turns jumping off the top rope of his shag couch for a smashing double-ax-handle like Macho Man Randy Savage.

Yes, we captive boys were the target market of the 1980s toy superhero trend. That meant a steady diet of televised ripped torsos and Technicolor cereals, filling our stomachs with rainbow-hued corn syrup and our minds with the muscley men of Saturday morning TV.

How was I to know that it was all a marketing ploy? Sure, Mattel had already Barbie, but in 1982, they demanded to reverse engineer a boys’ toy after seeing the colossal success of the Star Wars action figure lines. The cartoon show He-Man and the Masters of the Universe was created solely to sell the toys. And it worked, hitting a peak of $400 million dollars in 1986.

It certainly worked on us. James and I were ready to become heroes, creatures far better than our default weak selves. Of course, the strange twist of He-Man is that he didn’t really transform that much. Prince Adam had the same voice and haircut, and clearly had bulging muscles underneath his skin-hugging shirt. The only difference when He-Man raised up the Power Sword? Some lightning bolts popped his shirt off.

By the time I reached college, I was popping my shirt off every chance I could get. Never in public though. Always alone in my dorm room, scorning my skinny frame in the mirror. Ugly. Gross. Weak. At 6'3'' with frizzy hair and weighing only 185 pounds, I was a Transylvanian misfit (I blamed my mom’s Hungarian heritage). People told me I was lucky to have a fast metabolism, but it felt like a curse. To make matters worse, even when I bulked up, the gods double cursed me with disgusting iridescent pink stretch marks on my burgeoning biceps. Maybe it was all the creatine and weight-gainer shakes? But come on, there’s no such thing as gaining too much, too fast, right?

Though Rutgers University had 25,000 students, I kept company only with Conan and my childhood icons. Popping another late-night DVD into my TV, these were no unconscious kiddie consumptions. I’d gorge on midnight barbecue chicken cheesesteaks, gravy fries, dozens of Twix bars and Reese’s peanut butter cups, to the point of crippling stomach pains, all while actively telling myself: Yes. I am Conan, William Wallace, and Johnny Utah. And I’ll do better tomorrow.

In retrospect, this all tracks: my high-school friend had dubbed me a chameleon because of how easily I changed personas; I could shape-shift from an unshowering barefoot Grateful Dead hippie to a CK One cologne-spritzing club kid in no time. My self-membrane was always super squishy—a body with no border, like a photo of a ghost. Maybe this was why I was drawn to the squat rack? To feel the actual, physical boundaries of my body. To build myself up from a feeling of nothingness. If my muscles were pumped and defined, then I was more defined. I existed.

As a college gym rat lifting weights seven to ten times a week, my chest got bigger while my world became hyper small: chasing six-pack abs, extra lean protein, and fragile self-centered egoism. I was so alone and afraid of being rejected that I had to squeeze my stretch-marked arms before walking into a room. Though I worked out in a bubble, I wasn’t unique. Nearly seven million men will have an eating disorder at some point, most commonly binge eating. One in ten gymgoers will suffer muscle dysmorphia.

The relief switch for me? Numbing myself with more processed binge food, especially late-night sprees to the dorm room vending machine. The hardest part was hiding my obscene quantities. Even when successfully concealed within pockets, those mini packs of Cheez-Its simply became shame maracas. Every step and movement created a crinkling alarm waltz, signaling to passersby that I had an unforgivably abnormal number of cheap snacks stuffed into my pants.

How does someone slip further and further away in the middle of the bustling transformation that is the higher-learning microcosm? It’s easier than you think. At one point, I deliberately leaned into an experiment. “Don’t Speak” by No Doubt had been playing in the dining hall. My rule was: Don’t open my mouth and don’t use my vocal cords. I wanted to see how far the quiet went. It was a reflection of my thin sense of self, not some Zen vow of silence for self-compassion.

My experiment worked. For one month, I shut down my voice. I wore headphones all over campus, signaling that my “do not disturb” sign was hyperactive. I avoided eye contact, sat in the back of class, and politely nodded while holding the door open for my fellow students. I even stopped ordering takeout over the phone and did stealth runs for vending machine candy using extra baggy cargo pants to hide my shame snacks. No one noticed.

Eating disorders have been called the “silent scream.” Men especially don’t talk about it, which means that we’re lonelier and more isolated than ever, with the number of adolescent boys struggling with disordered eating on the rise. We bury it in the sneakiest of places—right on the surface. “Ha, yeah bro, no, I totally ate too much last night.” “Dude, I hate hotel food, my diet is shit.” “Yeah, no I totally gotta cut back on sweets.”

Listen to any casual gym conversation or two guys in line at Five Guys. We talk about it, even as we definitely don’t talk about it. Heaven forbid we actually say:

I really need comfort. I feel on all the time. I don’t know how to give myself something sweet. So I literally choose sweets. I eat it alone because it makes me feel good. I feel so ashamed and weak. I’m not supposed to be this comforted by something as stupid as a rainbow sprinkled ice cream sandwich. But they look so good on the box picture.

It’s not just men either. No one likes to talk about it. Not the real ugly feeling truth of it. I’m glad there are books, articles, podcasts and spaces for people to talk about this problem or any other. In that vein, Mr. Rogers’s message was wonderfully simple: Anything human is mentionable, and anything mentionable is manageable. Let’s wind that back for me. Because I couldn’t mention my bullshit back then, it definitely wasn’t manageable, and therefore I was subhuman. And in 2000, that’s exactly how I felt with my creatine and candy bars. Subhuman.

It took me years, with lots of backslides, and lots of help, until I found my way to healing and recovery. I think it’s time for men to share our vulnerability, starting with the body. If I had opened up more, I could have spared myself a lot of years of pain and anguish. I don’t know if I could have saved James. James and I had stopped talking at age fourteen. There was no breakup or defined moment. It was almost like we knew each other so well that our brotherly, sincere friendship couldn’t endure the artifices required of adolescence. Little boys are open and affectionate with each other, and then adolescence socializes young men to equate masculinity with strength, competitiveness, and stoicism. Putting on airs, talking about girls, being cool. That wasn’t us. And we couldn’t keep reading comic books and playing He-Man for obvious reasons. So we just stopped calling. Stopped coming over every Saturday afternoon.

I never learned what James thought of all this. He took his own life at age forty. It cracked open a chasm that I didn’t know existed. There was grief, anguish, love, pain, and unobstructed reality. I saw the real me, and the real James. I saw that deep down, we were always there . . . always connected . . . little boys burning with desire, shaping our future selves. Tear-filled waves of clarity washed over me. I knew what to do. Armed with my recovery, I was now a true warrior—aka a responsible adult, able to show up and be there for others. I flew to the funeral, comforted his family, and talked with James’s contemporary friends, learning about the man I never knew. Then I returned home and started writing our stories.

James and I had always wanted to be heroes. Even if part of us had been shaped by He-Man and the popular culture, it also resonated with our primal need, which is why Mattel was so successful. We perhaps mistakenly believed that heroes were supposed to help the helpless. You know, other people—not knowing we were the broken ones. Maybe we should have first looked inward. Anne Lamott has said, “Help is the sunny side of control.” I now know that there’s no saving others; at least, no rescuing someone from an inner struggle. Every day, I want so badly for James to be alive. Or for many men who are alive—who may be struggling in silence—to find their full selves before it’s too late. This stuff matters, and it’s all connected: masculinity, mental health, body image, and food.

Today, I’m so grateful to no longer be silently screaming. I also have the powerrrrrrr . . . to say no to a snack once in a while. To put my gratitude into action, I’m ready to keep my shirt on—and put my voice out there—in case someone wants to tune in.

A practicing lawyer in Vermont, Justin Kolber is a recovered ripped dude, an athlete, activist, and author of Ripped, the first memoir about the dual extremes of muscle and food disorders. www.justinkolber.com

I sent this to my college age son who is also a bodybuilder with an eating disorder and body dysmorphia. On the outside, he looks great, but on the inside, he’s hurting. Your piece acknowledges that guys aren’t immune to feeling lousy about how they look. The pressure is intense to fit in and to be “attractive.”

I appreciated your honesty and words. Maybe my son will read this. Maybe he won’t (odds are on the latter since he’s a college student and it’s a link from his mom, lol) but I read it and understood exactly the message. Thanks for that.

Thank you Justin. It’s so important for men to speak up about this. I’m recovering from a 40-year eating disorder, so I related to much of this.