The winter after my first fire season, before the summer I turned 21, my soul mate died of an overdose. I had driven him to the dealer’s house, taken the small white pills he offered for payment, glimpsed the flash of bright orange plastic, a bottle of liquid morphine, before he folded the paper bag closed. The pills were morphine, too.

Peter was 24. Long, straight brown hair. He called himself a pharmacist, a drug dealer with ethics who refused sales if he thought someone was addicted or harming themselves. Nothing soft, like pot. Pills. Cocaine. MDMA. He cooked his own ketamine into powder, slivering the solidifying liquid in a cast-iron pan. Kept GHB on the kitchen counter in a big plastic soda bottle. It looked dangerously like lemonade.

I dropped him off at his house, watching him close the rickety front gate, the wood planks long stripped of paint. It was raining. Winter in Eugene, Oregon. I swear it rained every day that winter. This was December, right before Christmas. A week later someone called for my roommate, Jonathan. “He’s out east for another week,” I said. They asked me to pass along the message. Peter had died of an overdose. When I started crying, they gasped. “You knew him?” I hung up the phone, crushed myself into the smallest shape my body would take, pressing my back hard against a sharp corner, so I could make sure I was solid.

I had been the last one to see him. “He was doing his monk thing,” someone said. After Peter closed the gate I drove north, to Olympia, where I spent a terrible Christmas with my mom and stepdad, who were drunk the entire time. This instead of accompanying Peter to the coast, like he’d wanted. Just us, a bunch of drugs, and a rented cabin. The gray sea, gray sky, gray sand. I loved him too much to say yes.

That doesn’t make sense.

What I mean is: I said no because the full force of Peter’s love scared me. The only love I’d experienced required absolute submission. I didn’t know this at the time.

For a couple months I woke up early, standing in line with a bunch of mostly older men at Labor Ready, where you could find temporary labor work and end the day with a paycheck. My affection for drinking to blackout and doing hard drugs inhibited me from holding down a straight job.

Peter had kept his drugs in a safe. His girlfriend, Ivy, had found his body. Before calling the police, she stashed them at a friend’s house. A few of us divvied them up into several Ziploc bags filled with smaller bags of powders and pills. Me and Ivy got high together most days, shuddering or melting, making out and rubbing our bodies together. I loved her. I can’t say what she felt for me. We didn’t talk much about anything, except Peter.

I learned how easy it is to burn through thousands of dollars’ worth of drugs, how fast it happens, and how, when the drugs are gone, the body longs for them so sharply.

Ivy auditioned at a local strip club. Sex work, if you can call it that, was familiar to me. I’d sold my body for money when I was homeless and underage. Is it still called sex work if you’re a minor? Only the men who bought my body knew it had a price. They used different words to describe me. Whore. Sweetheart. Little girl. I didn’t set out to sell my body, but one is either a hustler or hustled. I’m not sure which category I fell into. Maybe both. But neither was an informed decision.

I longed for fire season, for something to steal me away from the overhanging clouds, swollen and bruised. For light. For warmth. But fire season was months away. I borrowed Ivy’s little wrap skirt and leotard and auditioned at the club. They hired me, but not her. Our paths diverged.

Stripping gave me something to focus on. Like fire, there were clear rules and paths to success. The girls, first cold, warmed quickly, each of them rays of light refracting throughout the grimy dark club. I was used to working with only, or mostly, men. Now I worked with women, but we all worked for men. Our bodies were for their pleasure. Peter would have disapproved.

April came. Fire season was close enough for the contractor to call us in for some seasonal classes. I arrived late, underslept after a night of stripping and partying. The room full of men stared as I entered, and for a moment there was no division between the men in the club and in that classroom, my face still covered in heavy makeup, body sparkling with glitter beneath my giant t-shirt and baggy jeans. I had learned to see my body as currency. Stripping sharpened my nose for men’s hunger. The room stank with it. I could feel my own revulsion. My power that was not real power, because my body was not my own in their eyes, or the world’s. But it was the only power I knew how to wield.

I visited my mother in June. Fire season was slow, not like the year before, which had started in May. After draping a red velvet dress on my childhood bed, I held up my sparkly silver four-inch Pleasers, clacking them against one another. My mom, who had danced in Alaska before I was born, sighed. “You don’t have to do this,” she said, turning away.

“But I like it,” I said, setting the shoes down.

A few days later the club manager fired me for having visible track marks. My path had crossed with Ivy’s once again, in early May, but I was luckier than her. I had fire. Once the season started in early July, I was gone long enough to change course. On my days off I drank with a new set of friends, some of them firefighters. No more heroin. Sometimes I prepared a big bottle of GHB, but that was as far as it went.

Until September, when Ivy invited me over for a drink. We sat cross-legged on her bedroom floor. “Want to do some ketamine?” she asked, and I said sure, why not, thinking we would snort it. Instead, she loaded two syringes and tied off her arm, her movements completely habitual. I held my syringe aloft, watching her until she disappeared, slumping over. After a moment I leaned over and took the needle from her arm, released the band. I sat with her body. She was breathing, but it felt like I was alone.

A month later I left Eugene without saying goodbye to anyone. The following summer I became a hotshot, dragging my past behind me, an invisible sea.

This essay is part of Work Week, a series of essays related to work and career. Stay tuned for more this week, and see our Work section for past essays.

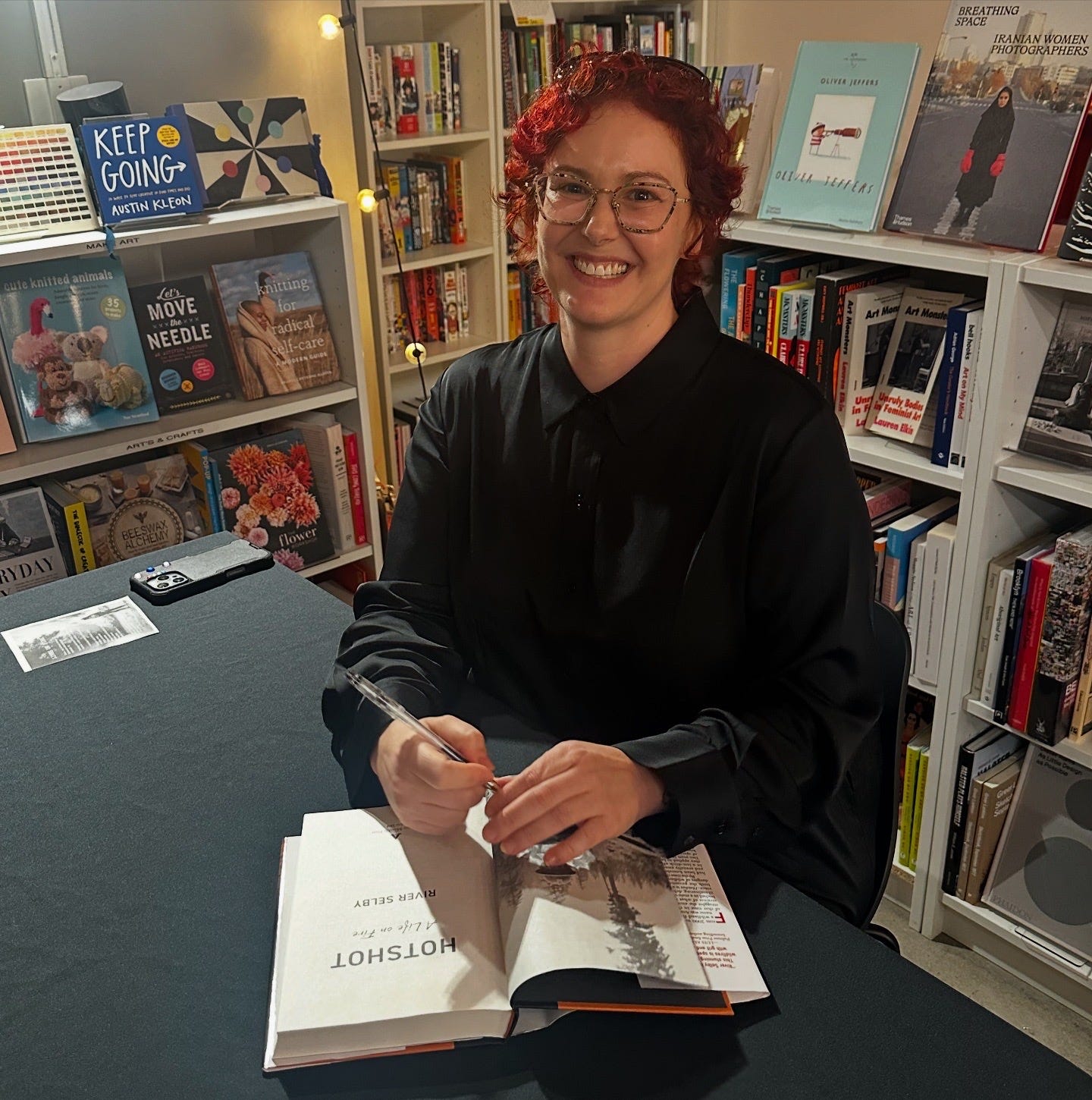

River Selby worked as a wildland firefighter for seven years, stationed out of California, Oregon, Colorado, and Alaska. They are currently a Kingsbury and Legacy Fellow at Florida State University, where they are pursuing their PhD in Nonfiction with an emphasis in postcolonial histories, North American colonization, and postmodern literature and culture. They hold an MFA in fiction from Syracuse University, and a BA in English and Textual Studies from the same institution, where they served as a Remembrance Scholar before graduating summa cum laude, with honors. River is the author of Hotshot: A Life on Fire, published by Grove Atlantic in August 2025. Learn more about them here.

What a great story, River. So engaging, visceral, and well written.

Thank you ❤️

Beautiful writing! A sad and captivating story... Thank you, River, for sharing your words!