In Grief, Mornings Were the Most Difficult Part of My Day Until I Remembered This

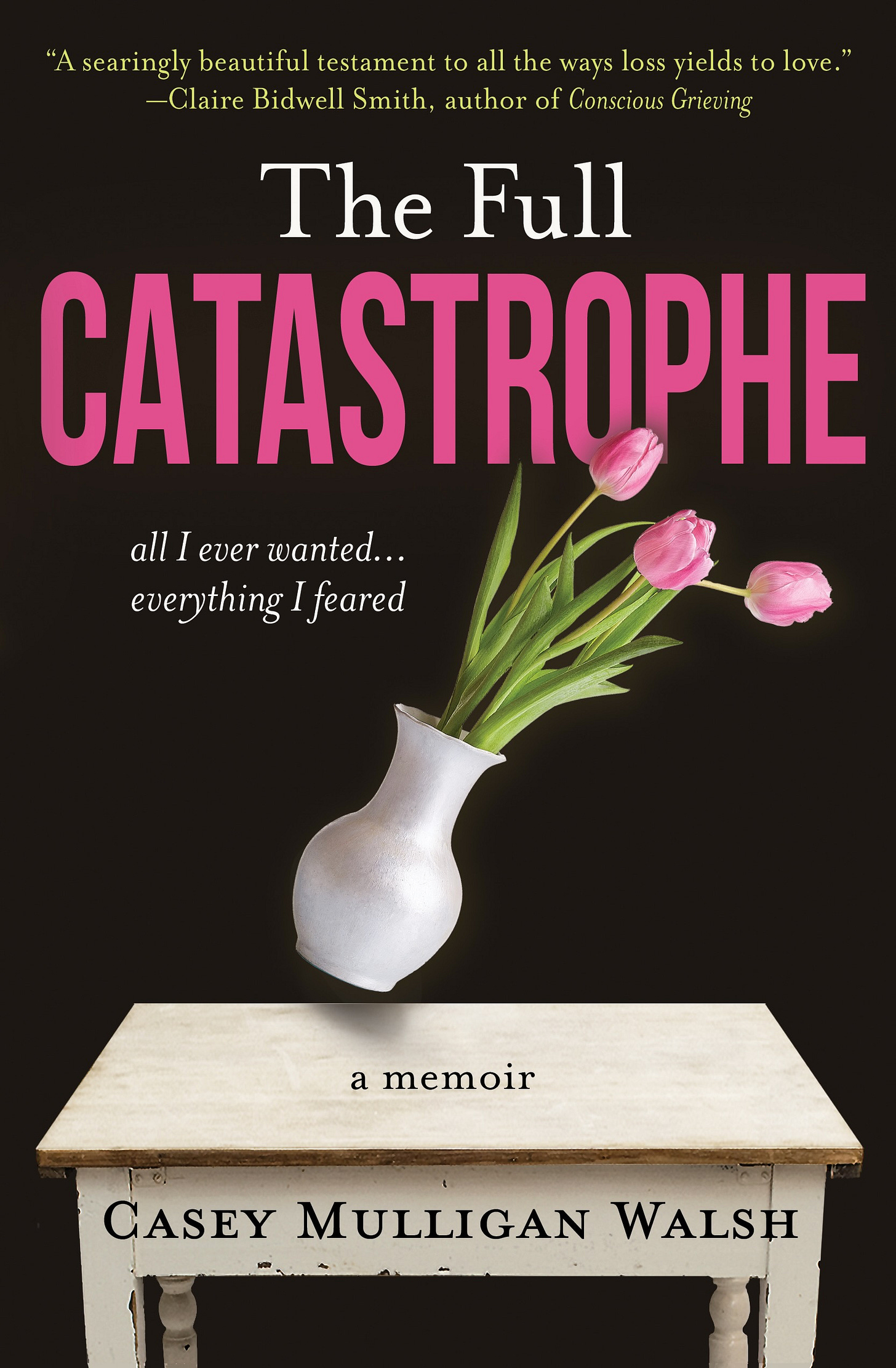

An excerpt from memoir 'The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared'

When I was deep in grief, mornings were the worst. People think the nights must have been the real torture, alone in a quiet house, with time to think and to brood, time to feel the darkness surround me and close me in. But during my most significant loss, I had a fix for that. I stayed up late into the night—two a.m., sometimes later—until I dropped into my son Eric’s bed in total exhaustion. I’d never had a sleepless night in the months following his death. Not one.

Mornings, they were another story. I remember that first morning, coming slowly to consciousness, becoming gradually aware of the relentless cooing of a mourning dove outside my window. It eased its way into my awareness, a soothing sound, it seemed to me. A trick. My body knew before my mind did, in that odd way our cells have of knowing. My eyes filled with tears, and I began to shake; my brain struggled to catch up. What had overcome me?

Oh. That was it. My son was dead. A rising panic, one I couldn't control, a wave I had only to ride until it was done with me, then the first pang of “why?” the dangerous question I’d not allowed myself to ask in fully conscious moments. For the first time, I truly cried.

It took my devoted friend no time to move from the sofa downstairs, where she’d kept vigil on that first night of unthinkable loss, to the bed beside me. She crawled in next to me and held me, and we rocked together until the grief had let me go.

That morning was both a magnified reflection of mornings past and a foreshadowing of many to come. Other mornings of grief before that one, when wakefulness had come slowly, were also accompanied by the gradual integration of another new reality. There were all the other deaths—my parents, my brother, the aunt who’d seen me through my teens, my late mother’s best friend who’d come to stay after the birth of my first child. This child, the one no longer with me. The grief those mornings had brought faded against the backdrop of this present loss.

But after a month or so, I’d seen that there was something else, something so different from those times before that it had taken me a while to recognize the pattern. It went like this: First, the warm, contented sense of coming back into the world from the cocoon-like safety of sleep. That lasted only a few sweet moments. Then, a punch in the gut, violent in a dull, drop-to-your-knees sort of way, brought on by traitorous brain cells that insisted on telling, on winning out over the ignorant comfort of the body. He’s dead they’d inform me. This is your life now.

I’d started thinking of it as my personal Groundhog Day, like the movie where the guy finally realizes he’s doomed to repeat the same events every day for eternity. I’d felt doomed, too, to live through being told, each morning anew, of this irreversible loss.

Once a hundred mornings or so had come and gone, it was no longer with every waking that I was blown over with the seemingly brand-new knowledge that my son was dead. A vague fear of mornings persisted, yet I found some kind of peace there, too, a peace I struggled to understand. Is it, I wondered, the simplicity of knowing I’ve gotten over the worst of the day right up front, that after this, things have to get better? There was some truth to this, but it still wasn’t the whole story.

Soon I began climbing the stairs at night to crawl into a sliver of my own bed, the rest of it taken up with piles of folded clothes. It hadn’t escaped me that I was occupying as little space in the world as possible, but I gave myself permission to re-enter at my own pace. Most nights, I retrieved a piece of Eric’s clothing from under my nightstand—a t-shirt, a jacket, his soccer jersey—one of the few garments from his hamper I’d had the good sense not to wash in the days after the accident. I’d hold it close and breathe him in as I fell asleep.

Now it seemed right to take a small step forward. I began by taking down papers and pictures and mementos Eric had taped to his mirror, folding and sorting his clothes. I unearthed a stack of photos from Christmases and birthdays and sleepovers with friends.

Into the storage bin they went, Eric’s favorite pants, those sneakers with the frayed laces, strawberry candy wrappers, crumpled bits of notebook paper with “Awesome Eric!!” scrawled across them, treasures from his younger years. Photos. His yearbook. I stashed away the detritus of his life until the far-off day when deciding what to keep, what to let go, would somehow be easier. For now, it was one small step, one breath, at a time.

In coming years, when I pictured Eric’s room just off the kitchen in this house where he grew up, I’d remember the unmade bed, the soccer posters, and the drafting table that hinted at a hopeful future. What I wouldn’t allow myself to fully reinhabit until years had passed was the dead weight of learning Eric was gone.

Yet even now, even in the depths of grief, I understood it. What we all need when our time here is finished is the love and forgiveness of those who remain to keep the best of us alive. This would be my gift to my son. This one thing I could do.

There’d been days those last couple of months when, amid the grief, I’d been able to find my way back to a place of calm. I’d resisted the temptation to fall into guilt or descend back into sadness—such an effortless drop. Instead, I resolved to take every peaceful moment as the gift it clearly was.

Then one morning, a revelation. Lying in bed, resisting the day, wanting just one more moment in that warm, comfortable place, I was struck with the knowledge that in this world of sleep—the world beyond the world—none of this had happened. This process of waking felt more like a birth than a death now, and, like birth, it came with pain. It was the journey from that safe, softened place where all is well, into the bright light of the world, where there’s no avoiding the harsh truth. Yet like birth, I’d survive the process and, if I was lucky, go on to embrace my life and the world of choices I did not make but must live with all the same.

And I thought of my son, who was with me now, in wakefulness as in sleep.

Reprinted with permission from multiple sections of The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared by Casey Mulligan Walsh.

Casey Mulligan Walsh has written for the New York Times, HuffPost, Next Avenue, Modern Loss, Hippocampus, Barren Magazine, and numerous other literary magazines. Her essay, “Still,” published in Split Lip, was nominated for Best of the Net. Her memoir, The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared, was published by Motina Books on February 18, 2025. Casey lives in upstate New York with her husband, Kevin, and too many books to count. Learn more at caseymulliganwalsh.com.

This is a beautiful excerpt, Casey. Those who don't know your beautiful book should indeed read the whole thing. ❤️

Same for me. Often people wondered if it was difficult for me to remember that my husband died and I would reply, "No, it is more difficult when I forget he died!" Fondly, Michael