Confronting a Second Grade Bully at Age Forty

How naming my relentless inner critic put me on a path toward healing

Therapy can be hard. You go in expecting breakthroughs and wisdom, but sometimes what you get instead is a weird question or a strange assignment that makes you roll your eyes before it makes any sense. And yet, in the middle of the emotional heavy lifting, something unexpectedly funny can happen, like being asked to name the voice in your head that tells you you’re not good enough. I wasn’t prepared for the answer that came out of my mouth, or the memory it unearthed.

“So you’ve said there’s a voice in your head. What does it sound like?” my therapist prompted during our second session. I’d reached out to David at age forty, desperate to figure out how to quiet the self-loathing that accompanied me through every waking moment.

“Well, it’s me,” I said after a minute of thinking. “I mean, it’s my voice telling me how much I suck, how I’m not skinny enough, or successful enough, or smart enough, over and over. It’s like a tape or film strip that keeps running from the time I wake up in the morning until I go to bed.”

He nodded. “Is the tape running when you’re at work?”

I almost laughed in response—it never stopped. “Oh, it’s running all of the time in an endless loop,” I said. “So even when I’m doing a presentation or leading a meeting, I have to try to quiet the voice on the tape and do the work I need to do. It’s pretty exhausting, and I wonder what it would be like if it wasn’t running. Imagine everything more I could do then. Just think about all of those gold stars I could get!”

I had told David about the gold-stars thing early on, and he knew how much I liked to achieve. As we got to know each other, I always tried to make him smile or laugh during every session, especially when I needed a little break.

He paused, considering. “Well, why don’t we try to give the voice a name, because even if it’s coming from you, it’s really just a side of you, and it might be helpful to name it,” he said.

“Like, a real name?” I asked. “What kind of name? Like Susannah or Percy or maybe Fleetwood Mac? How do I know what to call it?”

I was a little annoyed by this exercise because I wasn’t yet comfortable with our seemingly random circles and didn’t know to trust David’s methods, and sometimes I wanted those handy mile markers of progress.

“Can you think of somebody you don’t like, somebody who wronged you in some way? That could be a good way to give a name to the self-loathing for our purposes here.”

“SCOTT KENNEDY!” I shouted like a contestant on a quiz show. David looked surprised that I was so certain this could be the right name, but I knew it was.

Scott Kennedy. The red-headed boy from second grade at Chandlersville Elementary. He picked on me all the time, teasing me and chasing me on the playground.

One spring day at recess, I was on the monkey bars and he kept pulling my legs from below. I asked him to stop. He did it again and I asked him to stop again. The third time, I jumped down, pushed him to the ground, and pinned his arms down the way my brother did when he tickled me, but instead of tickling, I punched him right in the face as hard as I could. I’d asked him to stop picking on me, and he just wouldn’t listen. So I punched him again. Maybe three times. Mom had to come pick me up from the principal’s office, and she could barely keep a straight face on the way home. She again had to stifle a laugh when she shared over dinner that the youngest Gormley was sent home from second grade for beating up Scott Kennedy by the monkey bars.

I hadn’t thought about that kid for thirty years, and here we were, sitting in my therapist’s office in Manhattan talking about Scott Kennedy. I was laughing so hard at the memory, I forgot we were supposed to be working on something important.

David smiled. “So how do you feel about Scott Kennedy—the voice, not the kid you beat up on the playground?”

“What do you mean, how do I feel about him?” I asked. “He’s just always there, reminding me that I’m not good enough. I guess I’ve gotten used to it, and I’m still getting everything done in life. It’s just—God, it’s exhausting sometimes.”

“Well,” David prodded. “Do you think Scott Kennedy is right about you?”

I paused. “I don’t know. I mean, yes,” I answered. “I think he must be right even though I hate it—hate him—and wish the voice—sorry—that he would shut the fuck up and leave me alone.”

“Why don’t you stand up for yourself?” David asked. “Can you tell him to fuck off and leave you alone?”

It was a good question. “I don’t know,” I responded. “I’ve never tried, because I don’t know what I would say. I guess I agree with him when he tells me I’m ugly and not smart enough, that I’ll never really succeed, so I just try not to listen, but it’s always there. And yes, I know that by most measures I’m doing okay, that I’m attractive and successful yadda yadda, but I just wish I could feel good about myself. Does that make sense?”

“Yes, that makes sense,” David said, “but I think you’re missing something by not standing up to him.”

I sat there silently, wishing I could give David what he wanted but getting frustrated because I didn’t know how to do what he was suggesting, didn’t know how to feel something other than what I’d been feeling for so long. He saw my furrowed brow and after a few minutes suggested another method of understanding.

“So,” he said. “We know what Scott Kennedy thinks of you. What about other people who know you—really know you?”

“You mean like work people?” I started. “They all think I’m great—smart, funny, successful Sarah, the one you want to be your boss and the one you want to have drinks with after work. But I don’t think they count because they only see me at work.”

“Well, who else might you trust?” he asked. “You’ve told me about your DePauw friends. Do you think they really know who you are? I want you to picture them walking into your apartment, how they would greet you, and how they might describe you.”

I couldn’t talk because the tears started coming fast, hot streaks burning down my face, snot starting to drip from my nose. There were no words to describe my friends to David, what they meant to me, the feeling that came over me when I started seeing their faces one at a time as they came into my fancy apartment on West Twenty-Third, the one my Martha Stewart salary helped pay for, with the big terrace and views over the High Line and the Hudson River. Brooks, then Nancy and Tippett, Shawna, Hegman, and Fran. Fran with her sweet smile and “Hi, Gorms,” as she rounded out the crew. I could hear their voices, these friends of mine, my girls, and I could see them light up when they saw me, feel Brooks hugging me extra hard with one of her special squeezes at the end.

I was crying because David brought me there, right up to the place where I was going to have to acknowledge that the people who knew me best actually adored me. What I didn’t know yet was that even if you understand something intellectually, it can take years to let yourself believe it and even longer to let yourself feel it. And while I still have moments of being too hard on myself, I’ve learned to quiet my persistent self-critic, and I love that little girl who beat up Scott Kennedy more every day.

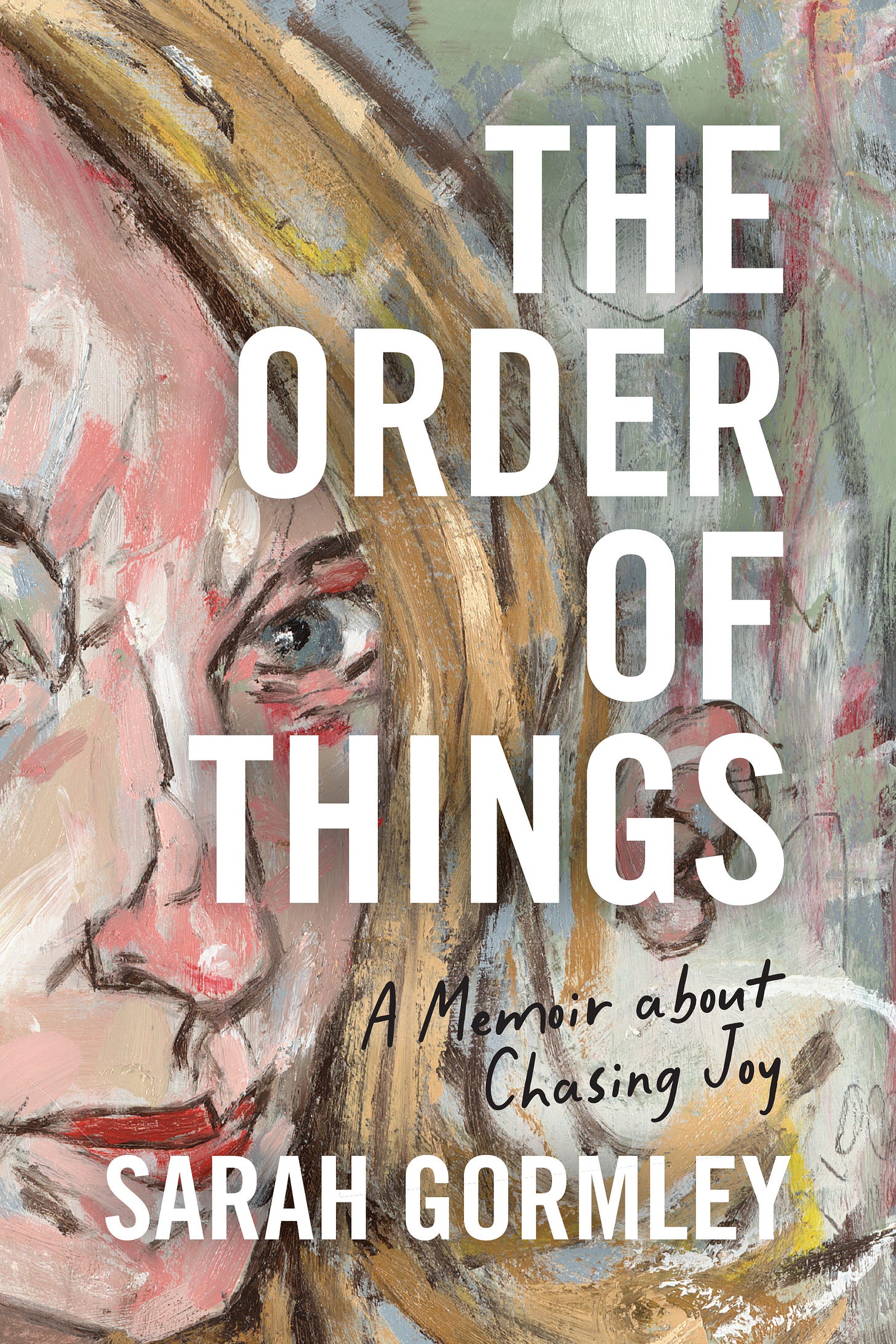

Parts of this essay are reprinted from The Order of Things: A Memoir About Chasing Joy (Salt Creek Publishing, 2024).

Sarah Gormley is a writer and art gallery owner living in Columbus, Ohio. Her undergraduate degree from DePauw University reinforced an early love for literature and writing, while the heavy sprinkling of liberal-arts fairy dust taught her how to analyze and articulate a clear point of view. She rounded out this foundation with concentrations in marketing and operations from the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

Today, Gormley owns a contemporary art gallery, Sarah Gormley Gallery, that operates from the belief that original art can be a source of joy for everyone and actively eschews pretense of any kind. She opened the gallery in 2019, twenty-five years after her Grandma Cameron gifted her with her first piece of original art.

Thank you. This really resonates for me right now. I'm 48, but I am a little behind where I should be as a “grown up”. I'm catching up in some ways..

I think the point I like that you made about it taking us years to actually believe things that we know, yet cannot put into action for ourselves.

I recently went through a near death experience and made drastic changes to how I perceive reality. It takes work. It's a fucking chore. But it's better than chronic panic and fear.

Beautiful! I saw myself in your writing, Sarah, which I think is the greatest gift you can give your reader, and more so since it's time on the proverbial couch. I feel like I just got a little hit of free therapy. Thank you Sarah!