My Dinner with Ruth Bader Ginsburg

A small-town attorney angsts about hosting an intimate dinner party for the iconic RBG

Note from Open Secrets Editor Rachel Kramer Bussel: Open Secrets publishes an original essay every Monday. We also publish occasional excerpts from recent memoirs I hope will appeal to fans of personal essays. We are a reader-supported publication; please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber to help Open Secrets continue to publish memorable, revealing personal essays about all the subjects we're taught to keep “secret.”

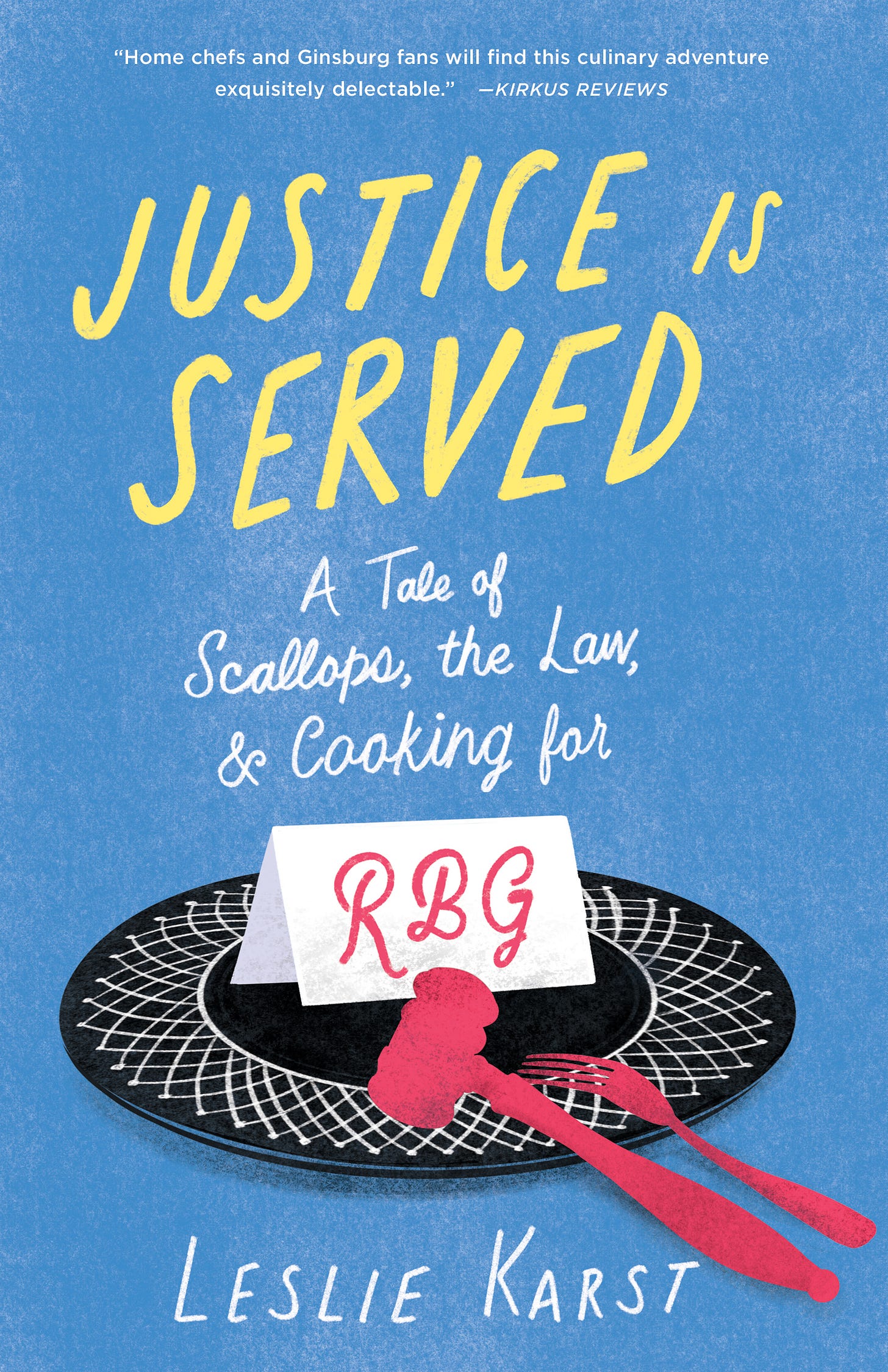

The following excerpt is from the memoir Justice Is Served: A Tale of Scallops, the Law, and Cooking for RBG by Leslie Karst (She Writes Press), available from Bookshop and wherever books are sold.

Chapter 2: Seasonable Doubt

D minus eight months.

The moment I returned to Santa Cruz from Paris, I was eager to write the Ginsburgs to find out if they had any food constraints, but I forced myself to hold off. It was only June, after all, and the dinner wasn’t till the following January. I didn’t want to seem that eager; that would surely be uncool. But there was no need to hold off on the bragging front. After all, hosting a celebrity such as Justice Ginsburg was truly something to crow about, particularly amongst my fellow attorneys.

Back in 2005, “RBG” was not the cultural phenomenon she is now, her face and dissent collar emblazoned across T-shirts and coffee mugs far and wide. And although I’d heard her name from a young age because of my father, it wasn’t until law school that I became aware of how truly important she was. When we learned in our constitutional law class what a fiery advocate she’d been during her pre-jurist years, I began to fully appreciate how central a role she’d played in changing the law of the land regarding gender equality—and how awesome it was that my dad actually knew her.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was, I now understood, a superstar in the world of women’s rights. And I was going to have the opportunity not only to cook a dinner for the justice but to spend an entire evening in her company.

Wow.

And Yikes! I thought as realization hit. Stopping in the middle of the sidewalk, I startled Rosie, who’d been trotting ahead of me on our morning walk. What the hell was I going to say to her? Dad would have no doubt told the justice that I was an attorney. What if she wanted to talk law with me? A shiver of apprehension passed over my body, and I shook out my arms to release the nervous tension now gripping them.

Here I’d been spending all my energy worrying about the food for the dinner but hadn’t even considered the conversation. Should I bone up on all the work she’d done as an attorney for the ACLU? Did I need to read about the cases that would be before her this term on the Supreme Court?

And then there was Ruth’s husband, Martin, who my dad had told me was a celebrated tax attorney in DC. With four lawyers in attendance at the dinner, not to mention the almost-attorney, Robin, it was a sure bet the law was going to come up in conversation—a lot.

But I’m not like them, I whined internally. I don’t really even like the law.

In fact, several years earlier, I’d become so unhappy in my work as an attorney that I’d come close to quitting. A blackness had started to greet me every morning when I awoke, and it had been getting worse. I’d lie in bed dreading the day ahead, wishing with all my might that I could call in sick or, better yet, simply give my notice and be done with it.

But then a strange thing happened. I was reading Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, the novel/memoir in which he’s scrambling to eke out a half-starved existence in depression-era Paris[i], and when I got to the bit where he takes on a series of pseudonymous writing jobs, it made me pause. For even though Miller loathed the gigs, he was thankful for the work, which allowed him to eat well for a time and—more importantly— continue his life in Paris.

It struck me that what Henry Miller had wanted more than anything back in his Paris years was to write. And even if it was ghostwriting someone else’s psychology thesis or hashing out pamphlets advertising a brothel, at least he was writing.

As was I, in my work.

I should be happy to be a legal writer, I reasoned—thrilled, even. There must be thousands of writers out there who’d kill for a job like mine. So why on earth are you whining?

It actually worked for a while. Because it was true. I may not have been working my dream job, but I began to appreciate how good I had it. Two of the things I loved most—besides food and cooking—were words and language, which were the exact tools of my trade.

Before long, however, the feeling of drudgery returned, and I was once again finding myself staring in misery at the legal casebooks spread out before me as I did research in our firm’s law library, wondering why I’d ever chosen this line of work. And now I was going to be on show in front of one of the most famous attorneys who’d ever lived.

A vision of the time I’d been asked about my moot court project during law school swam before my eyes—when I’d blanked out and couldn’t even remember the topic I’d been assigned for the damn brief. What if I had a similar episode the night of the big dinner and made a complete fool of myself? My stress level, which had already been sky-high at the prospect of simply cooking for the Supreme Court justice, now increased tenfold.

But I tried to hide it and returned to work after my Paris sojourn full of my news, collaring all the other attorneys at the law firm as they pulled files in the hallway or looked up statutes in the law library, to tell them about my upcoming dinner with Justice Ginsburg. If I could delude them about my anxiety, perhaps I could delude Ruth. Not to mention myself.

INTERLUDE

Martin and Ruth Ginsburg have provided different versions of why she ended up deciding to go to law school. He liked to recount that after the two of them became romantically involved at Cornell, they came up with the idea of following the same career path so they’d have each other to bounce ideas off of and would always have something in common to discuss over dinner. Marty started out as a chemistry major but had switched to studying government when the chem labs conflicted with his golf-team schedule, so medical school was out—as was business, since the Harvard Business School didn’t accept women. Therefore, by process of elimination, the Ginsburgs chose to pursue careers in law.

Ruth, however, told a different—and I suspect more likely true—story: Her undergraduate years at Cornell coincided with the Red Scare, when Senator Joe McCarthy was hauling people before the House Un-American Activities Committee to be interrogated for having belonged to socialist or communist organizations. After a Cornell teacher who refused to name fellow members of a Marxist study group was stripped of his teaching duties, the young Kiki Bader was horrified.

She had a professor of constitutional law at the time, Robert E. Cushman, who tried to make his students understand how the country was straying from its most basic values. He pointed out that it was lawyers who were standing up for these people, reminding Congress that we have a constitution that says we prize, above all else, the right to think, to speak, to write as we will without Big Brother looking over our shoulders. And so it occurred to Ruth that the legal profession would offer her the opportunity to get paid for her work and at the same time aim at something outside herself, to help repair the tears in society and make things better for other people.

Her family, however, was not pleased by this career choice because, as she put it, nobody wanted lady lawyers in those days. There was no Title VII[ii], and discrimination was up front, open, and undisguised. How could she possibly make a living? they worried.

But then, when she married Marty upon graduation from Cornell, her family’s attitude changed: Well, they now said, if Ruth wants to be a lawyer, let her try. And if she fails, she’ll have a man to support her.

So marriage, rather than hindering her career—as was the case for so many women of her era—helped advance it.

[i] I have a love/hate relationship with this book because, although it contains some gloriously poetic language and insightful looks at human nature, Miller also shows himself to be a narcissistic misogynist of the first degree.

[ii] Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.