What’s Queer?

Two queer Korean adoptees walk into a Korean adoptee event and one says to the other…

It’s summer, and my friend Benvy texts to ask if I want to go with them to a Korean adoptee event.

“Will we be the only queer people there?” I respond back because I already have misgivings. “I think so,” is their answer. I sigh out loud. Something makes me say, “Sure, I’ll go with you.” I haven’t given up on the adoptee community yet. But I know what’s in store because I have been to many of these similar events before, and they are always the same—cis-gendered, het Korean adoptee women, who bring their cis-gendered, het male (usually white) partners to what is commonly understood as “an adoptee only event.”

Benvy comes and picks me up the day of. We bring booze because we know we’re going to need it. Lots of booze. I think we had six bottles between the two of us. I’m silently musing this may not be enough, depending on how many people will be there. I ask, “Have you ever been to one of these before?” My friend answers, “No, I haven’t.” I sigh again, loudly. I’m trying to be positively open-minded because it’s been around eight years since I’ve attended one these and who knows how it will go? I know.

“Well, let’s hope for the best then.” I make small talk, asking them about their wife. We are both AFAB (assigned female at birth) adoptees, born in Korea, married to AFAB white women. I have a problem with this in my marriage for my own reasons, which will subsequently lead to divorce the next year, but I don’t know if my friend does. They seem happy and secure with each other whenever I’m with them. So I am happy to support my friend who wants to attend this type of an event for the first time.

We get to the house and are the first ones there. We can’t tell if it’s the right place, and as we walk to the front door, I notice the Christian angel statue under the doorbell. Uh oh, I think and point to it. Benvy nods and looks nonchalant. I take their lead and pretend everything is normal and that we are not about to walk into Christian hell.

A middle-aged Korean woman with natural streaks of white in her hair answers the door. We’re invited in and take our shoes off. The house is comfortably and traditionally middle-class decorated. There are family pictures above the roll top desk and on bookshelves. I’m trying to get a sense of the family who lives here. There are inspirational quotes tacked up on the wall, framed; some are religious. I inwardly groan. It’s all dark paneled wood and beige carpet.

Many things are bubbling on the stove and a large pile of vegetables is being cleaned. Our host knows her way around a Korean kitchen and looks prepared to cook a feast. Everything smells delicious and rich, like nothing but home cooking can. I love Korean food. I’m instantly grateful to this woman who invited me, a fellow Korean adoptee she doesn’t know, into her home, and is making all this food for the group.

I sidle up to her and try to make comfortable, non-threatening small talk, something I loathe doing as an introvert, but am adept at because of my experience and upper-middle class upbringing. I simultaneously gesture toward Benvy who has the booze. They silently acknowledge—we need wine! Our host begrudgingly climbs a step stool and brings down heavy cut crystal wine glasses, ones I assume she uses on rare occasions because they are on the top shelf, pushed way back in a cupboard. I clean them for us as she attends to the stew that’s bubbling.

Other guests arrive. Two other Korean adoptees. And of course they bring—what else—their white, older husbands. One is distinctly much older than his wife. I try not to roll my eyes. Or make a face. Not sure how successful I am. My disdain is sharp tasting. I try to hide it and shake hands with everyone but a fake smile is hurting my jaw because my teeth are clenched. I ask if anyone would like a glass of wine. I think I’m already going for my second glass. Or third. Benvy pours me more.

I step away from the counter to give myself room from everyone, and the oldest-appearing adoptee of the group heads toward the wine to pour her husband a glass. “What can I get you? Do you want white or red? Do you want it in this glass? Or how about this glass? Which one? Oh, I think you’ll like this one.” Her one-sided dialogue at him goes on like this for a while, the obsequious oozing out. Gaud, I’m such a judgy fuck. It makes my jaw hurt even more not to say, “You don’t have to do that. He can get the wine himself. He’s a grown-ass man, for fuck’s sake.”

And then it happens almost immediately once everyone has their libation. The inquisition. Instead of having a chat together in one group, it’s the same questions over and over again, from each individual adoptee and their husbands. Who don’t even have the grace to look uncomfortable or out of place in a room full of Korean women. The two men have the relaxed body language of entitlement.

One of them approaches Benvy, who is taller than me and doesn’t glower at everyone as I do. He hones right in on them and chats them up. They are a good sport and have been in the restaurant/wine business and definitely have more daily experience dealing with cis-het men’s gross behavior. I’m irritated that the men are even here, and it radiates from my posture. Oh, I’m not making any friends tonight!

In less than five sentences, I make my views on transracial, transnational adoption quickly known to the adoptee I’m talking to, stating it should be outlawed and that white people should not be allowed to buy black and brown children. That person gets uncomfortable, and we switch conversation partners again.

The older adoptee who was catering to her husband earlier asks me all the usual questions—how was I adopted, how did I get here, when, etc. I told her I was a private adoption, meaning my adoptive parents were in Korea and picked me out personally from the orphanage, just like a car or other things you can purchase from a catalog. Literally a catalog of children in black and white photos was what my adoptive parents flipped through. Her response is assumptive in its tone: “Weren’t you so lucky to be chosen specifically.” I recoil and shake my head adamantly. “No,” I counter. “My adoptive parents were monsters who had no business raising a child.” That ends another conversation.

The food is now ready. The men are outside BBQ-ing. Or verbally jerking themselves off. I can’t tell the difference glancing at them from inside the kitchen. I refill my glass and Benvy’s. I’m exhausted but trying to behave and be polite because that’s my white privileged upbringing kicking in again. Being around heteronormativity is exhausting. Being surrounded by essentially white women with Korean faces is even more exhausting. The internalized racism and being grateful to have been adopted attitude that pervades the conversations is grinding into me, as I continually hold the tension in my jaw.

We sit down to eat, and I stuff food in my talk-hole so I won’t say anything provocatively controversial. This isn’t the crowd. They’re still in the “Status Quo” phase, as described in the Adoptee Consciousness Model, which is believing the dominant narrative of adoption that employs only affirmative or positive-based perspectives about it.

But my breaking point is just around the corner. One of the husbands says something about how he can’t believe or understand what we all have gone through. No shit! How bad he feels for us. Seriously?! Blah blah blah. And then it clicks. He’s here for the trauma porn. He wants to be our daddy and soak it all in and be exalted for what a good guy he is and how he rescued his wife from the horrors (he already alluded to the horrors) she had to endure. What a guy. Let’s all metaphorically get on our knees and suck his dick right the fuck now!

I launch into my anti-oppression, anti-imperialism semi-rant. Because I don’t care anymore. I just do not give any fucks, especially about trauma porn dude getting his jollies. I state that I’m an abolitionist. And that we were lied to, and we are still being lied to by the U.S. government and the Korean government about our records. My audience is somewhat paying attention but I’m pretty certain I’m not going to be invited back. I sense one or two might understand what I’m saying because the odds are at least one of them has done a birth search, or at least knows someone who has done one, and most likely has been told a discouraging slew of lies that is nothing of consequence about their adoption.

We finish eating. The food is great. It tastes of homemade care and is well seasoned and fresh. The other three women have already met each other and know each other well. Benvy and I are the newbies. I circle back to the hostess to let her know again how much I appreciate her inviting us/me into her home and for cooking so much food. I ask about her process cooking certain dishes because talking about recipes is the only benign small talk I can handle at this moment. She then asks me how I know Benvy and where did we meet. I told her I’ve known Benvy for over 10 years and that we met at a queer meetup in the Bay Area.

Her response is, “What’s queer?”

“Gay,” I reply. “I met them at a gay meetup.”

It’s time for us to leave.

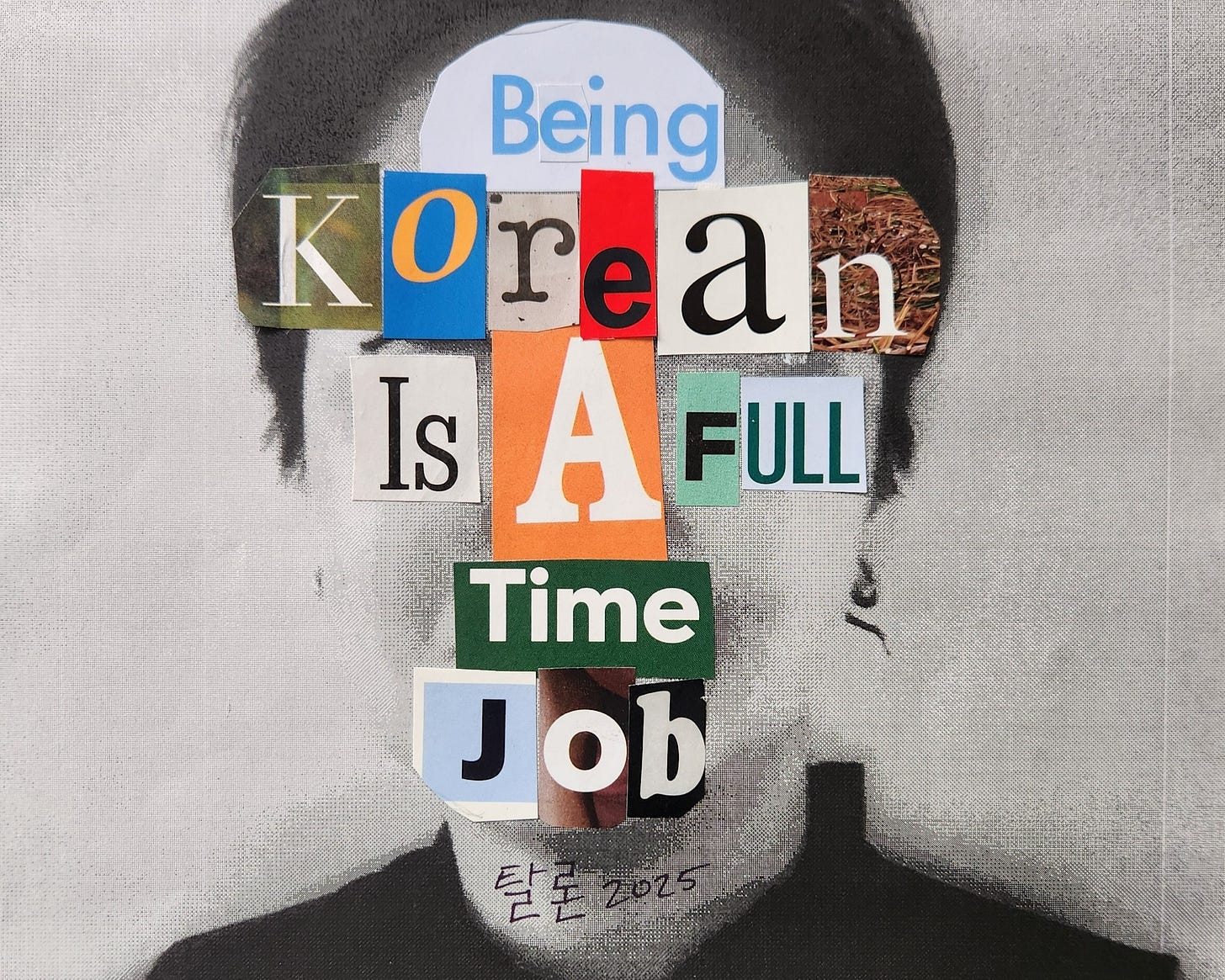

Talon (she/her) is a queer Korean transracial, transnational adoption survivor and found poetry paper collage artist who uses art as a form of resistance to disrupt the adoptee narrative. At the intersection of identity, lack of ancestry, adoptee sovereignty, and abolition, through her practice and writing she invites critical inquiry of white saviorism’s role in transracial, transnational adoption. Therefore her work is not just art; it is a catalyst, an attestation, and the belief in the power of transformation.

It’s strange how often we confuse rebellion with authenticity. There’s nothing subversive about mocking contentment.

Wanting love, companionship, a steady life, these aren’t signs of conformity. They’re human desires, no less valid than wanting to live differently. Rebellion loses its meaning when it depends on someone else’s peace to define itself.

Acceptance isn’t just about being seen at all. Maybe letting others exist in the quiet lives they’ve chosen, without making them proof of your own originality or visibility?

I will never understand this American thing of “buying” children to adopt and being even able to chose their ethnicity. In Europe you can’t give money to adopt and def can’t choose their ethnicity. You get what you get. The point is that you want to raise a child and take care of them, no matter their origins and skin color.

I’m not saying that we in Europe are better, but I agree that this stuff is crazy and should be made illegal (the “buying” children thing).