How to Thrive in an Analog World

On slow living, reconnection, and breaking the ice

On a Saturday night in January, I’m sitting in my bedroom waiting for over a foot of snow to fall. I’ve made all of the necessary preparations without crossing over the line of panic buying and resource hoarding. My car’s gas tank is full and the wipers are pointed toward the sky. I can see my SUV from the window and I’m already mulling over a de-icing schedule in my brain. All of my devices are charged and ready for any power outages and there are plenty of candles, batteries, and a flashlight in a basket on one of my nightstands. I’ve even made a bugout bag for my trunk just in case I have to leave. And I’ve checked in on my parents and sister, making sure at their respective homes in Ohio and Illinois they are ready to ride out whatever the next few hours are waiting to pour over our heads. I think I’m ready if the world suddenly blinks offline.

The block outside my apartment windows is quiet, all the cars lined up and the streets salted. Everyone, and everything, seems tucked in and anxious. I’m comfortable, warm, and calm. That is a feat in itself. It doesn't matter how long my city has been awaiting the snow, the entire world has been on edge. The social contract has ripped at the seams and all that we’ve tried to gather and fix and hide is now spilling out as each day passes. Comfort seems a rare luxury even fewer of us can afford than ever before. Safety, too.

While waiting for the storm, for the first time in years, I’m listening to the radio. The soft voice of the disc jockey is singing the praises of the Smokey Robinson song “Quiet Storm” that has just ended. I don’t know what radio station I’ve stumbled upon—it’s one of only four I’ve managed to pick up so far—but it’s a soothing mix of soul and uptempo jazz, like a 60s cocktail party. It’s the kind of music that lets you zone out and before you know it your shoulders are moving and time is slipping by.

As the disc jockey chats about the upcoming set of artists, I realize that I’ve missed the vignettes of music history and lore that come between the songs on stations like these. The immediacy I’ve gotten used to via streaming services is absent. On the radio, there’s a gentle fade out between songs, maybe three or four of them played in a row, before the voice over the frequency comes back to connect with listeners again. It’s a much slower pace and I’m not sure how I’ve gone so long without experiencing music this way.

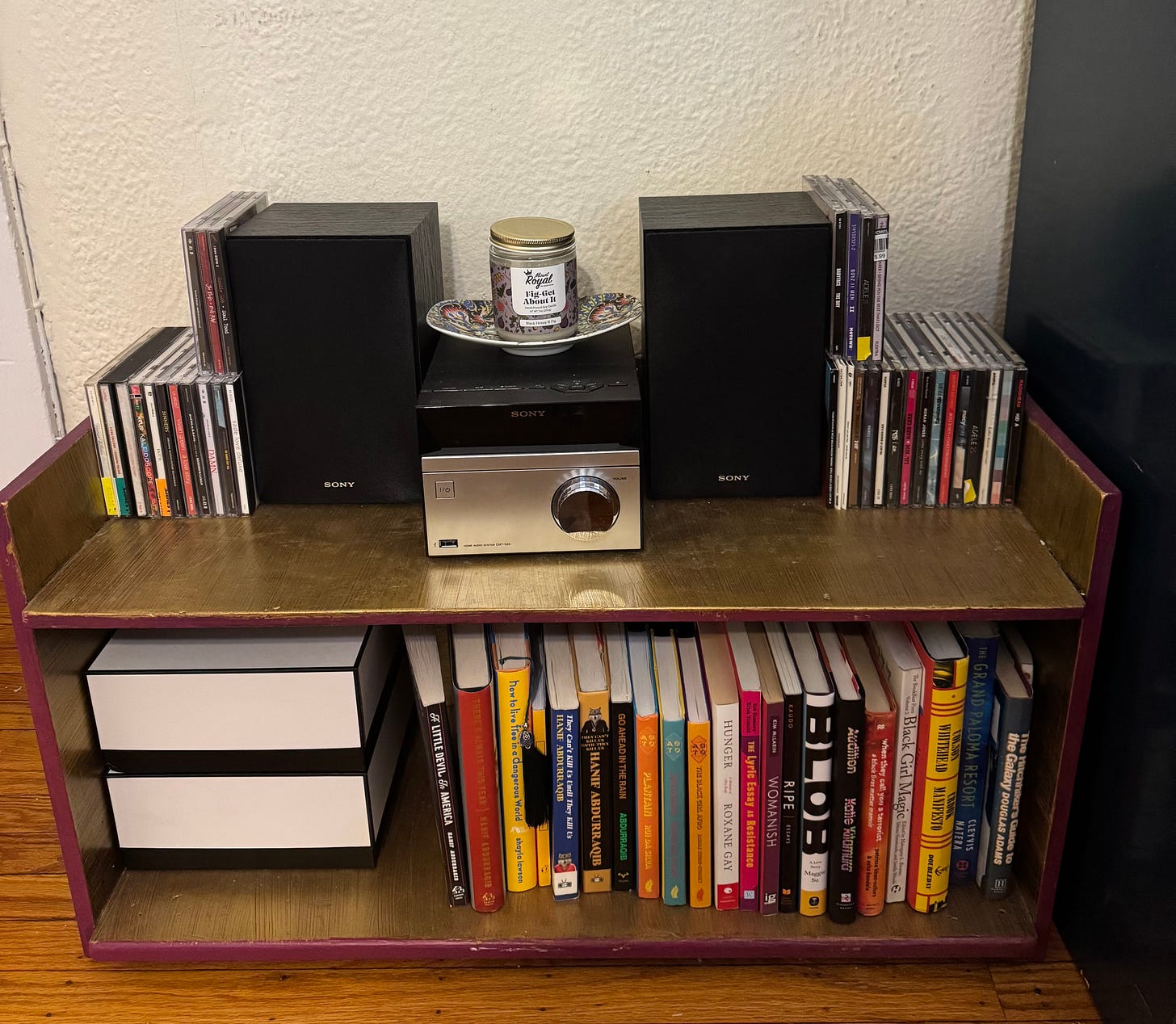

A few weeks ago, while meticulously scanning the books in my apartment to create a digital library of what I own, I decided I wanted to invest in a vintage home audio system. I scoured eBay for one that hit my desired budget, need for actual speakers, and the aesthetic I was seeking. Of course, the dream system I’d grown up seeing in videos was now vastly overpriced due to the resurgence of all things 90s and 2000s being cool. So I settled on a sleek mini system with two speakers and that slightly futuristic vibe that permeated my middle and high school years. When it arrived in perfect condition, I set it up in my bedroom right near my bed with visions of lazy mornings and evenings listening to CDs dancing in my head. Until I realized I had exactly zero CDs to test out this new desire. So I listened to the radio while I sent me and my sister on a quest to rebuild the collection of physical media I’d once been so proud of.

The analog world I’m creating isn’t perfect, though. The system I selected could pick up more radio stations if I was willing to unfurl the antenna wire and trail it along the wall, but that ruins the aesthetic. So I think maybe I stumbled across the perfect station and that’s all I need. As the night rolls on, and the snow has yet to start, the station has switched to soft Latin tunes full of percussion and brass. I can only pick up a percentage of the words, but I’m still soothed by what I hear. Even the new jockey slips in and out of Spanish during the transitions. The songs are long, looping into and over each other, until I look up and an hour has passed. I get up to check outside and run my fingers over the books on the built-in shelves in my bedroom. I’ve been on a mission here, too. I’m not just cataloging the books I own; I’ve also been collecting the physical catalogs of all the independent Black authors I love, directly buying from them when possible and on Amazon as I have to, because I’m afraid that in this current world one day I’m going to log into my Kindle account and poof!, the books I love will be gone even if I’ve paid to own them.

It’s become important to me to keep physical copies of Black history texts and critical theory as moments, mentions, and monuments of my people are being erased in real time. Just two days ago, I watched videos of placards outlining the history of slavery in the area being removed from the President’s House exhibit in Philadelphia. The administration says we cannot disparage those in the past. We must show our nation’s glory, our achievements. But collectively owning generations of people and milling them down to bone and spirit is achievement, right? Pretending that the ripple effect of that grinding down doesn’t still wear their ancestors smooth so they can’t quite get a grip like yours do is an achievement, right?

I wonder about the Spanish on the radio, even the words I don’t know, and how quickly they can be erased. How quickly the bodies that make the voices can be swept away and buried. I wonder what the world sounds like without these voices. It’s becoming reality now. I don’t have to wonder what the world sounds like when the voices are knocked out of harmony and instead they are screaming for safety, compassion, justice, fairness, and basic human decency. It’s reality now. Two days ago, there was a little boy in a blue hat being led away, pulled from everything he’s ever known in the dead of winter. This city, and many across the nation, have been freezing for months now. And then a little girl. They show her in pink on the news, her little face smoothed over like there was Vaseline on the lens. Captured in an innocence that can never be again.

It’s not snowing yet but it’s cold. Or maybe it is snowing, but unless you’re looking you don’t notice it. The city prepares for nights like this; the meteorologists warn us what to do in advance. They tell us to clear the streets, to only travel when necessary. The roads are dangerous, they say, covered in ice. You have to be careful where you walk because any little slip-up and you’re falling and no one can help you.

But that’s not necessarily true. It snows for hours once it begins. The snow and ice pile up so quickly that it seems an impossible task to dig out from their weight. But then my neighbors start to appear one by one from lighted doorways and down the steps of apartment buildings. The percussion and horns keep playing in the distance, the soft Spanish of the disc jockey explaining the significance of the songs, as I gaze out the window and hear the shovels start to break through and hit ground. At first the people work solo, digging around the tires of their cars and one man taking his snow blower to the sidewalk to create a path to his home. But then he clears a little further, expanding the path so he’s not the only one safe from falling. He makes a plan for the rest of us, too.

I let the radio play until my eyes feel heavy and the music switches again to classical. In the morning the snow has stopped and the block is quiet. But then it starts again. People come out and start digging and digging until soon a few cars are able to leave. People mark their spots with chairs and tiny tables and a singular, bright orange traffic cone. The neighbors respect the hard work it took to make progress against the snow and so even when the cars leave the block we hold space for them. In the morning snow, I see people I never knew lived in the houses and apartments around me. We work side by side, our breath white in the air, fingers freezing, until soon enough of us have fought back against the snow and the ice that we’re moving forward again. We refuse to be trapped on this block, in this moment in time. The city isn’t coming to rescue us. There’ve been no plows, no more salt to melt anything away. It will take us to set things right.

When the sun goes down, I listen to the radio again. The jazz starts first and then the lilt of the Spanish tunes fades in and after a few hours the concertos and symphonies pick up. All the while, the sound of shovels and digging persist. A few voices rise as people greet each other or offer help. When the sun comes up the next day, the block looks clearer than it was before, the snow and ice beaten back and still receding.

Athena Dixon is the author of essay collections The Incredible Shrinking Woman and The Loneliness Files and her work appears in publications such as Harper’s Bazaar, Shenandoah, Grub Street, Narratively, and Lit Hub among others. She is a Consulting Editor for Fourth Genre and the Nonfiction/Hybrid Editor for Split/Lip Press.

I really like the "communities coming together to help each other because the powers aren't going to do it" of both the snow shoveling and rising up against ICE and the authoritarianism going on in this country. And interwoven with that, a beautiful nostalgic feel, with the radio station reminding you of a less impersonal (at least with some things) time. I didn't say that well, but please know that your essay is rich and lovely.

Loved reading this, thank you.